How would you rate your listening skills? Do you struggle with communicating with art buyers or gallery directors? Are you involved in leadership in an art-related organization? When asked to speak to a group about your art, how comfortable are you?

In 2017, a man that I met at my church invited me to attend a Toastmaster’s meeting. I was vaguely aware of Toastmasters, knowing that it involved public speaking. I decided to attend. I became a member because I saw the activity would help me grow in ways that I needed and could not obtain elsewhere. At the time, I was in transition from part-time Radiologist and part-time artist to full-time artist.

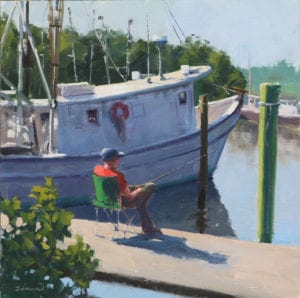

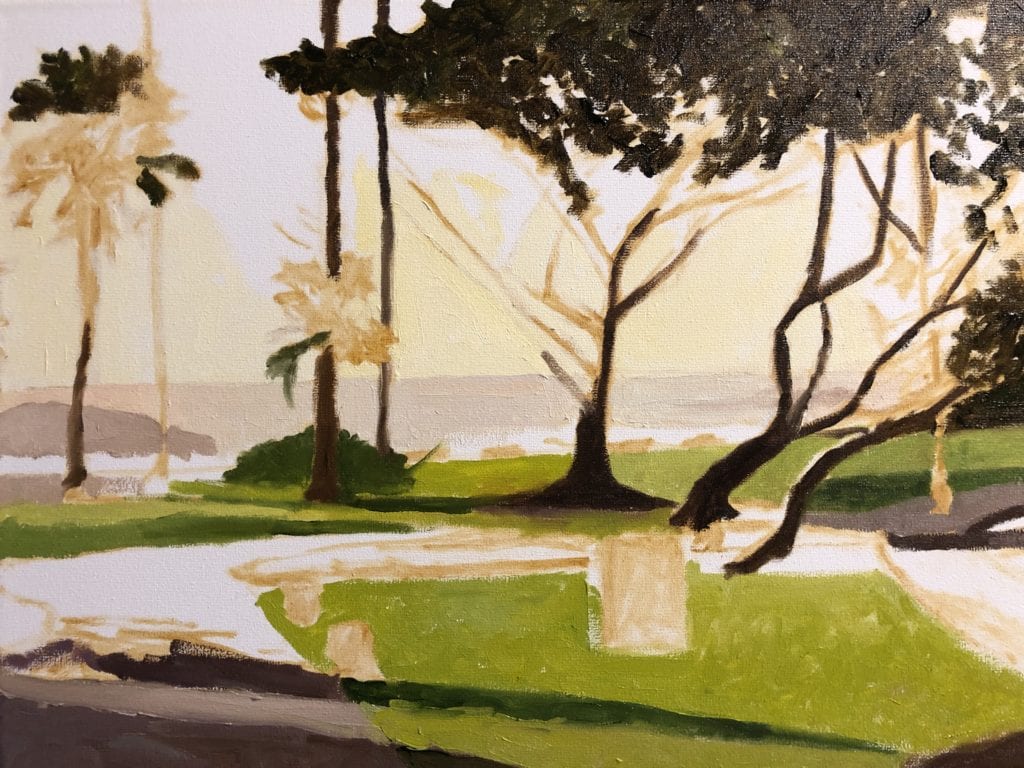

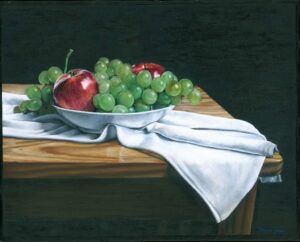

24″ x 24″

As a physician, I thought I knew a fair amount about communication. After all, for 40 years I had been giving people bad news or explaining a procedure and it’s potential complications. I had given numerous talks over those years with positive feedback. I had accomplished many roles as a leader.

However, after joining Toastmasters, I realized that I had been approaching the whole process backward! My order of priority was: Leading – Speaking – Thinking – Listening. I thought that if I was a strong leader then I would be able to speak with authority and convince people to trust me. I doubt that anyone would have described me as a good listener.

In Toastmasters, I learned that the correct order of priority is: Listening – Thinking – Speaking – Leading. Many people may think that the sole focus of Toastmasters is public speaking but the Toastmaster’s motto is: “For better listening, for better thinking, for better speaking, we learn by doing”.

One of the roles that members have in a meeting is to be an evaluator of the speakers. It is impossible to be a good evaluator if you are not a good listener and observer. It is impossible to accurately assess human interaction without being a good listener. When you listen to someone, do you think about making eye contact? If you are looking elsewhere, what does that tell them about your level of interest? Do you respond with positive facial gestures? Do you wait until they finish before speaking or do you interrupt them? Do you jump right into responding or do you take time to think?

In our fast-paced world, we have to think fast. In Toastmasters, we learn to think fast but also to how to focus on what to think about. An evaluator has only a few minutes to organize their thoughts and give a verbal response. We learn how to give effective feedback according to a system. The system focuses our attention and organizes our thoughts.

In one segment of the meeting called “Table Topics”, we learn to think at warp speed. At first, I hated this segment but I have come to appreciate its value. The Topics Master presents a topic and calls on individual members to give a 1-2 minute talk on that topic. You have about 15 seconds to think and start speaking.

It is only after listening well and thinking well that you are ready to speak. It is only after speaking well that you are ready to lead well. The two main goals of Toastmasters are to communicate effectively and to lead effectively – in that order.

How is this related to the artist’s life?

How well do you listen? One of the aspects of speaking that I had given no thought to before Toastmasters is body language. You encounter potential buyers of your artwork, art patrons, gallery directors, and art students. How aware are you of their body language and your own?

Did you know that your body language influences trust more than your words? Have you not met someone that you did not trust but could not say exactly why? Your subconscious (what we refer to as “our gut”) is assessing the other person’s body language. A good listener brings that subconscious evaluation into their conscious thought process. They do it by consciously evaluating body language.

For instance, if you approach someone and they take a step back, are you consciously aware that you have invaded too far into their personal space? When you explain something to someone and they cross their arms, are you aware that they don’t trust what you are saying? Do you observe what the other person is doing with their hands? It may surprise you how much we communicate with hand movements. This is why people find it hard to communicate without moving their hands. Do you often stand with your hands in your pockets or behind your back? Are you aware that this communicates that you have something to hide? Are you aware that standing with your body oriented at 90 degrees to someone else is a defensive posture – showing a lack of trust? How often does your body language contradict your words? When this occurs, people believe the body language, not the words.

After listening to your potential client or student, do you take time to carefully consider what they said? Do you respond to only the words you heard or also to the body language you observed? As you respond, are you consciously aware of your own body language?

If you have a leadership role in an organization, your effectiveness will depend on being a good listener, a good thinker, and a good communicator. Effectiveness as a leader or communicator depends on trust. Effective leaders and communicators ask themselves: Do they trust me? If the answer is no, then you have to find out why. Why is this potential client not comfortable with commissioning an artwork? Why are they hesitating to buy? Why is the gallery director not promoting my work? Why is the student not trying the technique I showed them? Why is my audience not making eye contact with me?

At some point in your art career, someone will ask you to give a speech or make a presentation about your work. How much do you desire to be an effective speaker – to communicate an idea or concept that your listener will trust? Most people fear public speaking more than they fear death. Is that true of you?

Toastmasters will enable you to be a better listener, thinker, speaker, and leader. It is fun! It will broaden your contacts. It will introduce you to people who will help your career in unexpected ways. The new online Toastmaster’s Pathways program allows you to choose the learning path that best meets your needs. Your area will likely have many clubs to choose from that may have different emphases. You can attend up to 3 meetings for free at individual clubs.

Find a club near you at www.toastmasters.org

Book References: “Trust Me” and “Power Cues” by Nick Morgan.

Contact Ken Requard: kenrequard8@icloud.com

www.kenrequard.com