We want to be alive, energized, and excited about life and our growth as an artist. Is there a process based on current psychological science that makes it easier to attain and sustain higher energy in our lives and our art? Are there ways around fear and boredom? And, is the process accessible to all of us? The resounding answer is “yes” based on science.

Awareness, curiosity and focused processes (effort not talent) will blast through limiting stories and beliefs that have taken root in our unconscious. Einstein was a big believer in curiosity and imagination and concluded everything is energy. Robert Henri maintained “art is a footprint of a life well lived.” Books by Harvard and Stanford professors lay stepping stones for high achievement. If through awareness you find your inspiration (what you would love to say in art), use your imagination (how you would want to say it in your own authentic voice), and take motivated action through a process (flow) both intrinsic and extrinsic results can be achieved. How?

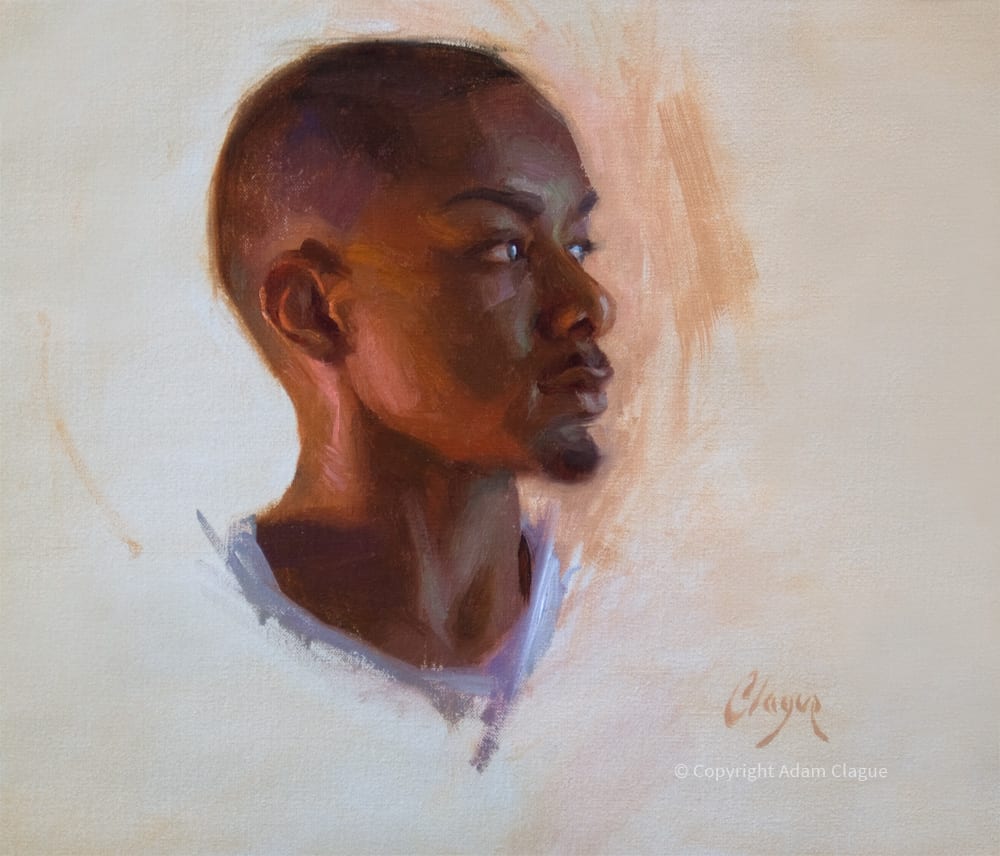

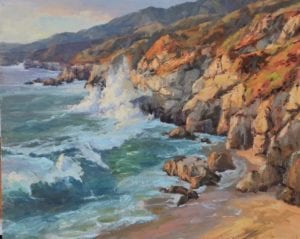

Oil on linen – 24″ x 30″

First, increase your curiosity about you, become

Second, alter your perceptions to enjoy the process. The journey will always be there, and you never reach THE pinnacle. The journey can be motivated by fear, or by inspiration, imagination and motivated action. IT IS YOUR CHOICE AND IN YOUR CONTROL ALONE. Your primary motivation to create art should be intrinsic benefits, e.g. it will give you pleasure and meaning, not primarily extrinsic benefits like sales quotas. (HINT: there are lots of motivators at one time, the key is what is primary.)

Third, explore your inspirations. Focus primarily on intrinsic inspirations vs extrinsic. Why? Because they are the only things you can control and they alone create sustainable happiness. John Wooden, the UCLA coach won 10 out of 12 NCAA titles. A feat that has never been equaled in any sport. His primary thrust was to inspire his players to perform to the best of their ability; he never told them to win. Wooden stated after his career that what he missed the most was team practices. He was solely focused on the process in the journey. The art world is similar to other careers, it has its share of unfairness, nepotism, prejudice, clicks, pandering, and egotism (surprise). Control of enjoying your journey is only within you.

Fourth, imagining your successes will make you feel really great, but it won’t achieve anything. Studies show you must both imagine successes AND overcoming obstacles to them. For example, how will you achieve enjoying the easel for ____ hrs a week? You must change your perspective from art is work to it is a privilege, a meaningful joyous process filled with discoveries allowing you to birth your authentic voice, it gets you in a flow, a mentally healthy state, not to mention the many satisfying connections with people.

Studies show that challenging growth is a pillar to sustainable happiness and as the founder of the Montessori schools said, “nothing is more relaxing than engaging in an agreeable task.” Hedonism does not lead to sustainable happiness. Motivated action from inspiration and imagination excites you to paint. You will have something exciting to say if you are living with a curious energy. And according to Robert Henri if you have something to say you will find a way.

In “The Achievement Habit”, by Bernard Roth, a professor at Stanford University, Roth says to always err to the side of action, even when not 100% sure of direction, he states more answers are found in action. According to Tal Ben-Sahar, a professor at Harvard, perfectionism is unhealthy, so act and do the best you can. (HINT: Don’t get lost in abstract ideas like a great piece of art is always better than the sum of the parts or that you are creating universal symbols or how will you be judged.)

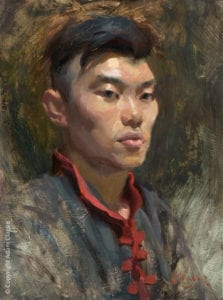

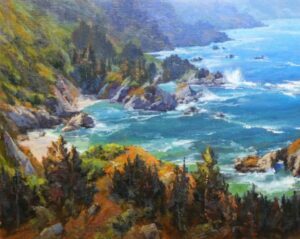

24″ x 30″

Imagination is a key to growth. Think of how you would love for your painting to look and imagine better and new ways for you to express your authentic voice. Go beyond your boundaries and limits, it excites because its risky and edgy and prevents boredom. Try new tools, change shapes, colors, textures, scrape off, repaint. Make many mistakes, the more mistakes the faster the growth. Mistakes are not failing but learning opportunities, quitting the exploration process is the only failure. (HINT: watch great videos, and get in a supportive environment and attend positive workshops that encourage curiosity, discovery and exploration and where no one ever judges you (check with past students to verify the teacher is great), and the teacher pushes you beyond your limits. Great teachers inspire, are genuinely concerned you grow, explain the why and pour out every tool they have to help you, and yet require you to do the work.

Like all growth, your ability to recognize great art rises as your awareness increases; savor great art. Study it, live with it. After a while we all become competent enough to paint a scene, later you will inflict more of your authentic artistic voice with more of your imaginative skills and it will be richer. If you keep exploring and trying new things your repertoire of tools will increase. You want the attitude of hell yeah I am going to (not trying to) paint this new way. It may take a while for new methods to advance from crapola to really cool so perceive it as an exciting journey.

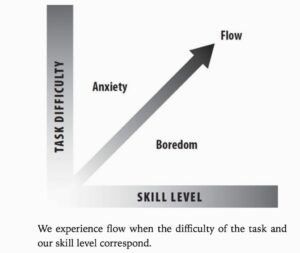

New processes need balance. Too much growth is anxiety and too little is boredom, the perfect balance is flow, which is a joy-filled journey.

“Happier: Learn the Secrets to Daily Joy and Lasting Fulfillment” by Tal Ben-Shahar

When reaching a certain level of accomplishment you start to get somewhat serious about your work and the excitement may start to dwindle. The antiserum is to bring your “old learning playful Beginner” back in to sit alongside the somewhat accomplished “Experienced You”. This Beginner was who got you started and who knows how to enjoy the process. The best beginners had little judgment and took many risks, therefore accelerated growth.

The Experienced You naturally has a bit more ego and naturally becomes more concerned about what others think. The antidote is to go deeper into yourself and what you can control. Wooden’s teams were trained not to focus on the other teams, he did little scouting but instead focused on what they could do to become the best they could be. It’s

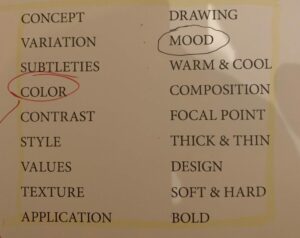

Since this book is out of print, I leave you with James Reynolds comments on what this renowned artist thinks makes a good painting.

The above guidelines are useful aids and other tools from more advanced artists always make painting easier, we can all learn something from everyone. I enjoy discovering how workshop attendee artists learn quicker and easier. As I watch and develop I discover more tools that make it easier on me and students. The interesting thing is there are always new ones waiting to be discovered. A great quote by Joseph Cambell author of the learned book “The Power of Myth”, “the big question is whether you are going to be able to say a hearty yes to your adventure.”

Always be risking new things so the adventure is off the charts. Live on the edge and create art that goes a little farther and a little different, that is where to find the adventure and excitement. Do not deny the world the opportunity to bask in your brilliance.

For more tips on attitude, click here for Bill’s other blog posts.